Does our perception of public spaces change during quarantine? What new meaning do parks and healthcare infrastructure acquire? These and other questions can be examined through the example of Hannover — one of the greenest cities in Germany, where the main value lies in the richness of its natural environment.

Public space in times of isolation

Since mid-March, Lower Saxony, like other parts of Germany, has introduced restrictions due to the spread of COVID-19: all public events were banned, cafés, restaurants and almost all small businesses were closed — except for shops and pharmacies. At the same time, people were allowed to walk around the city with family members or in pairs. In the absence of familiar entertainment — restaurants, exhibition centers, and clubs — the importance of parks, squares, rivers, and other natural areas became particularly evident. Normally, the quality of the urban environment is defined by the variety of its public spaces, but during the pandemic, parks became the new centers of social life.

Fig. 1. Georgengarten Park. 12 minutes by bicycle from the city center.

In the first weeks of lockdown, people mostly stayed at home. Yet as the weather grew warmer, they naturally began going out for walks — especially as many had more time for it. Sports, cycling, rollerblading, scootering, walks with children, and fishing became practically the only available forms of leisure. Whereas before people gathered for picnics or sports in large groups, now the disciplined residents began to keep their distance.

A city shaped by nature

Fig. 2. Georgengarten Park. 12 minutes by bicycle from the city center.

It is worth noting that Germans in general prefer to live away from the city center, in private houses close to nature. Many therefore had the opportunity to spend lockdown in comfortable conditions. Unlike countries with strict quarantine regimes, Germany did not limit freedom of movement, and a simple walk was never perceived as a privilege. The new reality proved quite comfortable for a city like Hannover, with its well-developed and diverse green spaces.

Fig. 3. Rooftop bar with a view of the New Town Hall, city center.

Hannover is not the most famous, but a relatively large city by German standards. In Germany’s largest metropolis — Berlin — lives only a third of the population of Moscow. As the capital of Lower Saxony, Hannover is in northern Germany and has a population of about 532,000. Within the wider metropolitan area, around 1.2 million people live there. The nearest major cities, Hamburg and Berlin, are only an hour and a half to two hours away by train.

According to the Morgen Post ranking, Hannover holds seventh place among the greenest cities in Germany with a population of over half a million. It also ranks eighth for its large medical clinics. The population is made up mainly of doctors, civil servants, pensioners, students, and families with children. It is a calm, comfortable, and stable city — hardly a place for fast business, start-ups, or hustle. Despite being home to the headquarters of major international companies such as TUI, Continental, Volkswagen, and Rossmann, and despite hosting the Hannover Messe exhibition center, there is no relentless pace of a large metropolis. On the contrary, Hannover is ideally suited to a healthy and measured lifestyle — something that proved particularly relevant in times of global economic slowdown.

Fig. 4. Square in the Linden district where the Volkswagen commercial was filmed. 8 minutes by bicycle from the city centre.

The garden city legacy

Life in Hannover combines the advantages of both urban and natural environments. Half of the city outside the center consists of private residential areas. More than 65% of Hannover is green space, which means there are about 250 square meters of greenery per resident. Two small rivers — the Ihme and the Leine — flow through the city center, while a navigable canal circles the city. In the south, there is a district with more than forty lakes. Parks, squares, and avenues — the main types of public space — cover the entire city evenly, including the historic center.

In Germany as a whole, nature is regarded as an unquestionable value, and discussions about the need to protect it continue constantly at both political and civic levels. Sometimes there are even surprising rules: for example, in Hannover, killing a wasp can result in a €5,000 fine, as they are a protected species. So, in summer, when entering a bakery, one often sees pastries covered in wasps — and no one reacts. The safest option is to buy something sweet early in the morning, as Germans, after all, are early birds.

Fig. 5. One of the lakes in the southern part of the city. 22 minutes by bicycle from the city center.

The idea of the “garden city”, proposed by Ebenezer Howard in 1898, naturally comes to mind when thinking of Hannover. Howard’s model of the ideal city for 32,000 people placed a park at its physical and conceptual center. The key value of the garden city was its ecological balance — integrating housing and public infrastructure into a natural setting through green belts. Since 1903, many such cities have been built around the world — in the UK, Sweden, Germany, Spain, Israel, Australia, and Russia. In Australia, for instance, the capital city Canberra, designed by Walter and Marion Griffin, became known as the “bush capital”.

Fig. 6. Plan of the Australian capital Canberra (left) and the “garden city” concept (right). Source: Urban Planning Library

Green systems and architectural identity

Hannover was never designed as a garden city, yet in essence it evolved into one naturally. On the map, one can clearly see the central part of the city with built-up areas separated by green zones. A ring road — the “City Ring” — encircles the city center. Following this road, as well as through parks, forests, and riverside paths, one can travel around the entire city within the green belt without entering the motorways. Even in central districts, allotment gardens are common, so it takes only 20–30 minutes of walking from the center to feel as if you’ve left the city. In such conditions, self-isolation feels more like a holiday.

Fig. 7. Houses facing the Eilenriede Forest in the List district. 9 minutes by bicycle from the city center.

The reflection of the natural environment can also be seen in Hannover’s architecture. The city has entire neighborhoods of Art Nouveau houses, recognizable by their flowing forms and decorative plant motifs. There are more than three hundred such buildings, yet surprisingly little information exists about this cultural heritage. Only a few examples were featured in the exhibition Architecture as Medicine. Most of these Art Nouveau houses are residential buildings found in every district of the city.

Fig. 8. Passive houses in Wettbergen. 23 minutes by bicycle from the city center.

In keeping with sustainable development, construction was completed in 2018 on the Zero:e Park residential district in Wettbergen. Using passive-house technology, it reduces CO₂ emissions by 75%, with the remaining emissions offset through compensation programs.

The connected landscape

Fig. 9. Fields of rapeseed in Ahlem. 24 minutes by bicycle from the city centre.

Hannover’s greatest value lies in its landscape, and the key feature of its green areas is their connectivity. The ability to move across the city through continuous green corridors makes social distancing easy. Hannover has neither “concrete jungles” nor narrow medieval streets. The highest density of buildings is found in the city center, which includes only about ten high-rises up to 100 meters tall. Most streets are lined with trees or front gardens. The city has around 45,000 trees, and between 500 and 750 new ones are planted every year. When trees are lost due to drought or natural decay, the event makes local headlines. The city administration removes damaged trees for safety, but this often sparks public protest — so since 2002, a Society for the Protection of Old Trees has existed, and each tree slated for removal must be inspected by an expert.

Fig. 10. Trees in Georgengarten Park. 12 minutes by bicycle from the city center.

The vegetation in Hannover’s parks is arranged like an artist’s palette: light-green foliage stands beside the purple crowns of cherry plums, white apple trees, yellow cassias, red maples, silvery plane trees, lilacs, pale pink magnolias, bursts of red tulips across lawns, and wildflowers and grasses along the rivers. Such rich park landscapes can rival visits to a museum in their range of impressions. Hannover resembles an open-air landscape museum, complete with its own “Monet’s Flower Island”, “Duck Pond”, or “Renoir’s Spring”.

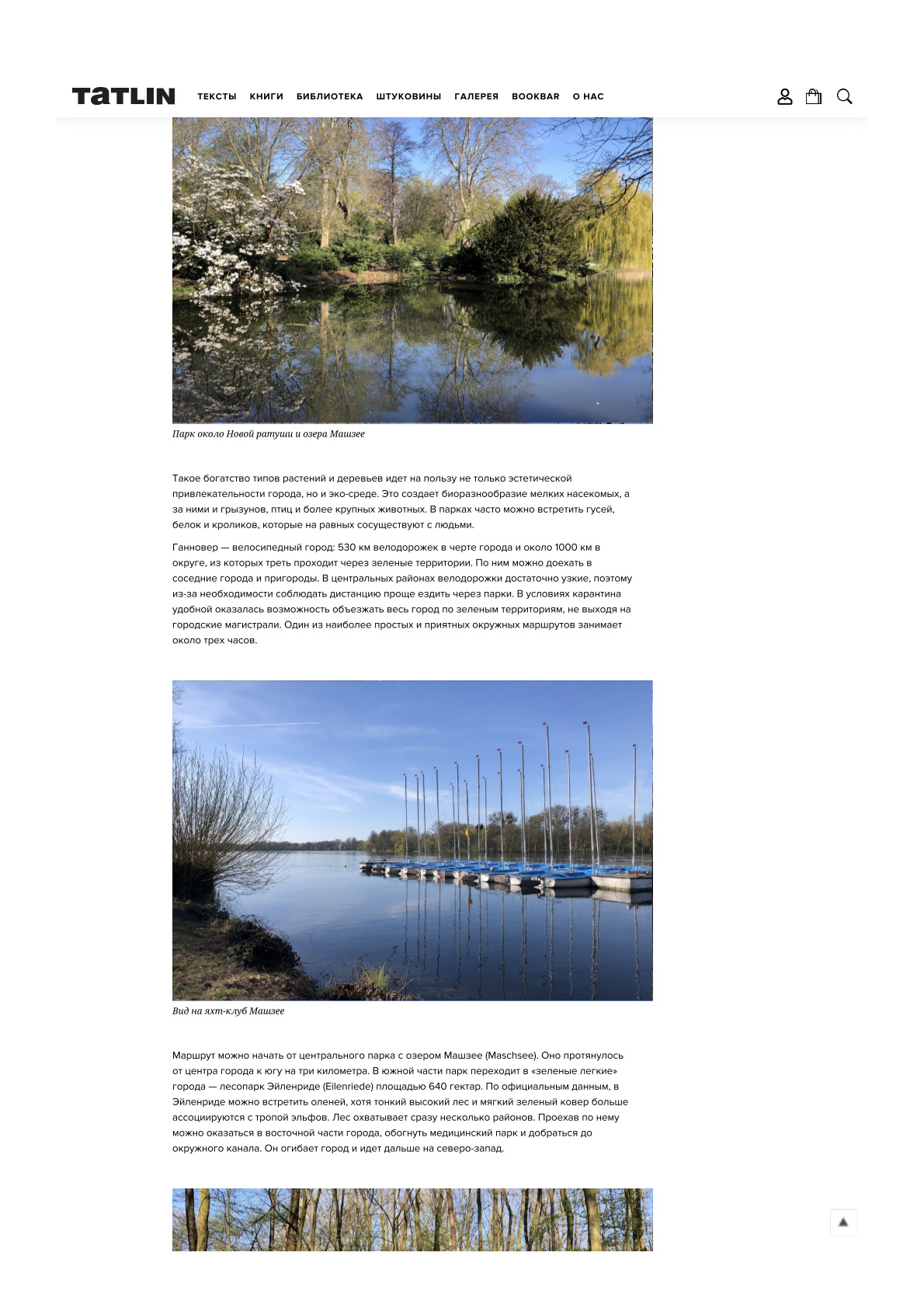

Fig. 11. Park near the New Town Hall and Maschsee Lake.

This variety of trees and plants benefits not only the city’s beauty but also its ecological balance. It fosters biodiversity — attracting insects, rodents, birds, and small animals. Geese, squirrels, and rabbits coexist peacefully with people in the parks.

Movement and mobility

Hannover is also a cycling city: within its boundaries there are 530 kilometers of cycle paths, and around 1,000 kilometers in the region — a third of which run through green areas. These routes connect the city to neighboring towns and suburbs. In central areas, the lanes can be narrow, so during lockdown it was often easier to cycle through the parks. One of the simplest and most enjoyable circular routes takes about three hours.

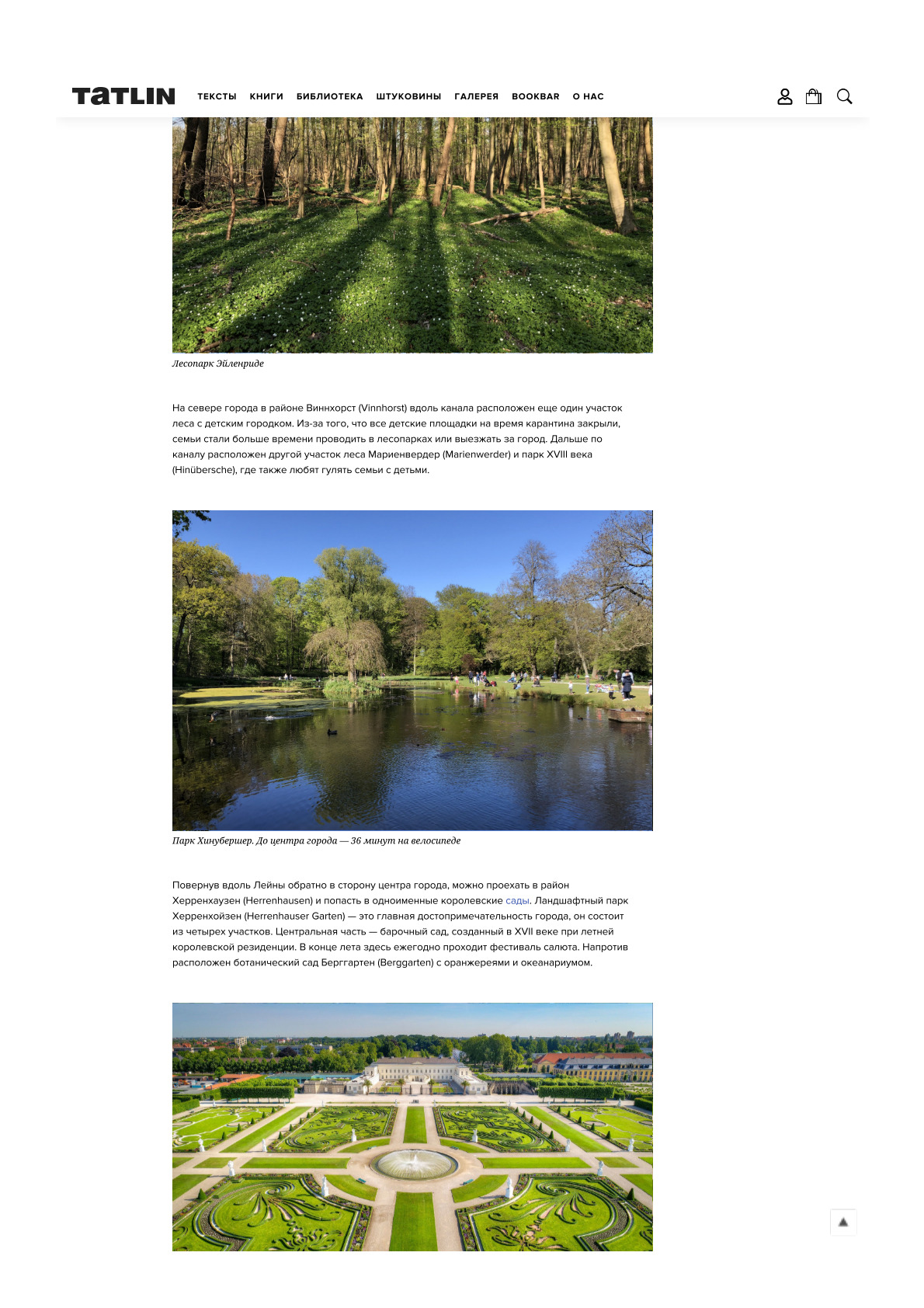

Fig. 12. View of the Maschsee yacht club.

The route can begin at the central park and lake, Maschsee, which stretches three kilometers south from the city center. At its southern end, the park merges into the “green lungs” of the city — the Eilenriede Forest Park, covering 640 hectares. Officially, deer live there, though its tall slender trees and soft green carpet evoke the path of elves. The forest spans several districts, leading to the eastern part of the city, past the medical park, and towards the surrounding canal that continues north-west.

Fig. 13. Eilenriede Forest Park.

In the north, in the Vinnhorst area, another stretch of forest with a children’s playground lies along the canal. Because all playgrounds were closed during lockdown, families began spending more time in forest parks or venturing outside the city. Further along the canal lies the Marienwerder Forest and the eighteenth-century Hinuebersche Park, both popular family destinations.

Fig. 14. Hinüberscher Park. 36 minutes by bicycle from the city centre.

Turning back along the Leine River towards the center brings you to Herrenhausen, home to the famous royal gardens. The Herrenhausen Gardens are Hannover’s main attraction, consisting of four parts. The central one is a baroque garden created in the seventeenth century beside the summer royal residence, where a fireworks festival takes place each late summer. Opposite lies the Berggarten Botanical Garden with its greenhouses and aquarium.

Fig. 15. Royal Gardens. 15 minutes by bicycle from the city center. Source: European Gardens.

A two-kilometer avenue then leads towards the city center, passing the Leibniz Institute and the Georgengarten Park, named after King George IV of England. Normally, the Herrenhausen gardens attract large crowds for walks, picnics, open-air concerts, and sports. During quarantine, visitors became fewer, but it remained one of the city’s favorite public places. Cycling along the Georgengarten and following the ring road or the Leine River, one can return to the starting point at Maschsee Park.

Fig. 16. Summer royal palace of Herrenhausen.

Historical layers and urban continuity

One of the key reasons behind Hannover’s comfortable urban environment is its stable historical development. The city began to form at the end of the twelfth century and received city status in 1241. In the fourteenth century it joined the Hanseatic League, which stimulated population growth and trade. As the capital of the region, Hannover avoided major destruction until the bombings of the Second World War.

Fig. 17. City panorama, view from the New Town Hall.

Not being a center of political or economic power, Hannover nevertheless developed as a royal residence, maintaining a high quality of life and a well-planned environment. The city’s structure, formed over various historical stages, includes both organic layouts and regular grids. In the nineteenth century, under chief architect Georg Laves, many significant buildings were constructed: the main railway station, the opera house, Georgsplatz, Königstrasse, and others. Laves worked on the city’s development for fifty years, adhering to the neoclassical style.

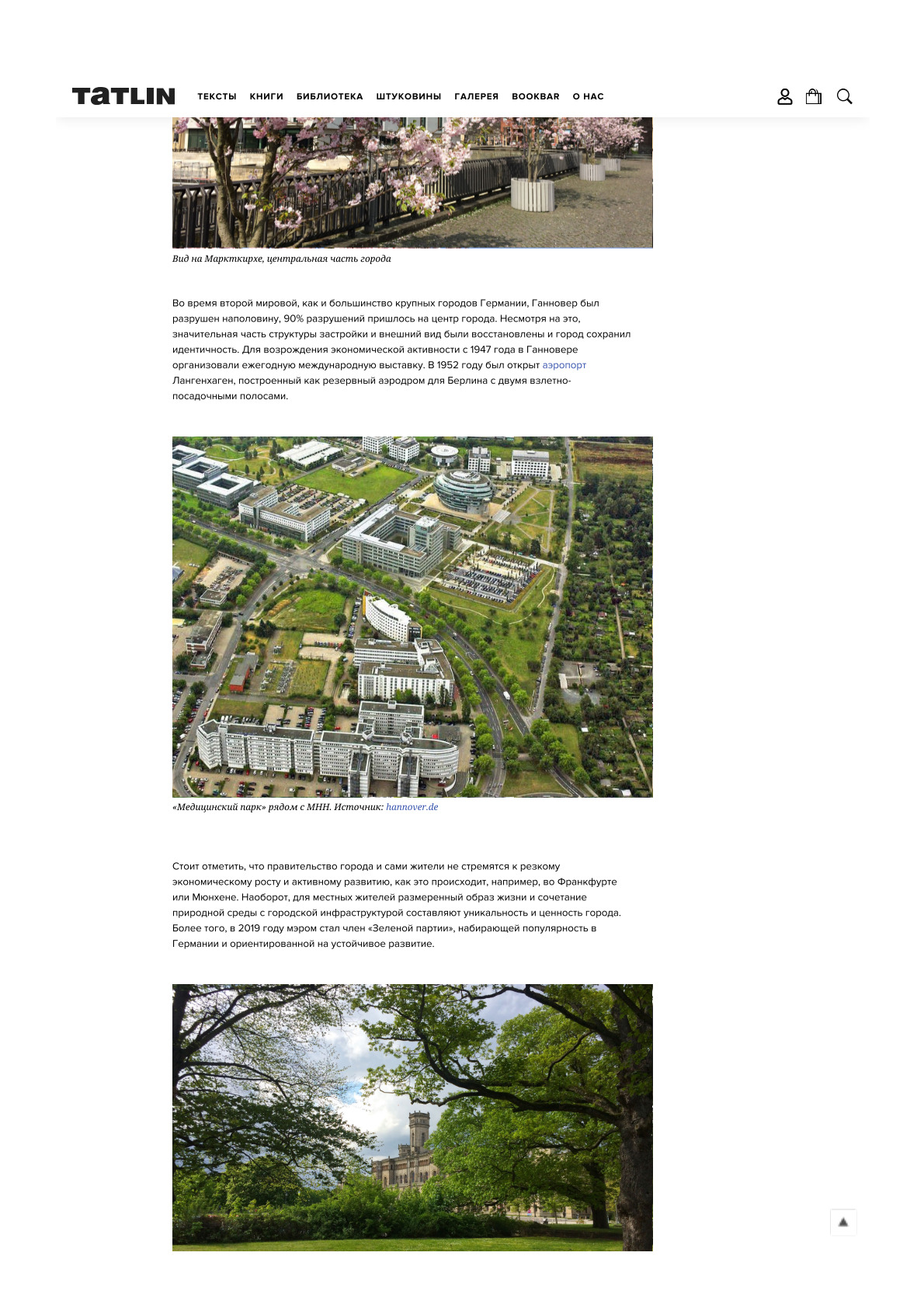

Fig. 18. View of the Marktkirche, central part of the city.

During the Second World War, Hannover was half-destroyed — 90 per cent of the destruction occurred in the city center. Nevertheless, much of the urban structure and appearance were restored, and the city retained its identity. To revive economic activity, an international trade fair was launched in 1947. In 1952, the Langenhagen Airport opened — originally built as a reserve airfield for Berlin with two runways.

Fig. 19. “Medical Park” near MHH (Hannover Medical School). Source: hannover.de.

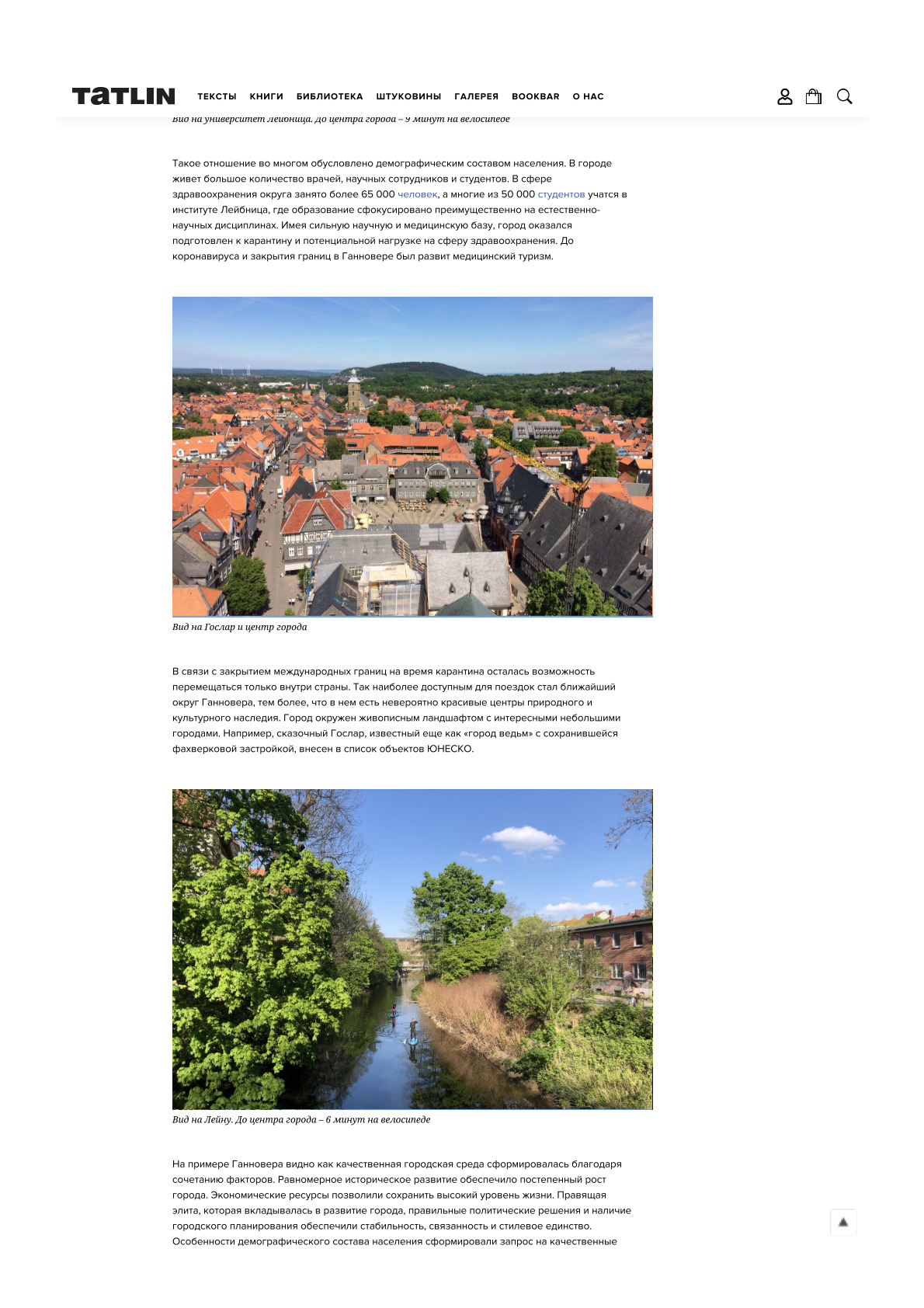

It is worth noting that the city government and residents are not seeking rapid economic growth or intense development, as is the case in Frankfurt or Munich. On the contrary, a calm pace of life and the combination of nature with urban infrastructure form the unique identity and value of Hannover. Moreover, in 2019, the city elected a mayor from the Green Party, which is gaining influence in Germany and promotes sustainable development.

Fig. 20. View of the Leibniz University. 9 minutes by bicycle from the city center.

This attitude largely reflects the city’s demographic composition. Hannover is home to many doctors, scientists, and students. More than 65,000 people work in the healthcare sector, and many of the 50,000 students study at the Leibniz University, which focuses primarily on the natural sciences. With its strong scientific and medical base, the city was well prepared for lockdown and the potential strain on its healthcare system. Before the pandemic and border closures, Hannover had also been a center of medical tourism.

Fig. 21. View of Goslar and the city centre.

With international borders closed, travel remained possible only within the country. The Hannover region itself proved ideal for short trips, offering remarkable natural and cultural landmarks. The city is surrounded by a picturesque landscape and charming small towns — for example, the fairy-tale town of Goslar, known as the “city of witches”, with its preserved timber-frame architecture and UNESCO World Heritage status.

Fig. 22. View of the Leine River. 6 minutes by bicycle from the city centre.

Reflections and lessons

The example of Hannover shows how a high-quality urban environment can emerge from a combination of factors. Gradual historical development ensured steady growth; economic resources maintained a high standard of living; wise political decisions and urban planning preserved stability, connectivity, and stylistic unity. The city’s demographic composition created demand for quality services and strong healthcare. Altogether, these elements have shaped a city designed for life — a city with a soul — where work and leisure remain in balance. Large enough to support business and industry, Hannover still allows residents to focus on the fundamental values that have become especially important in the new reality: family, health, and the environment.

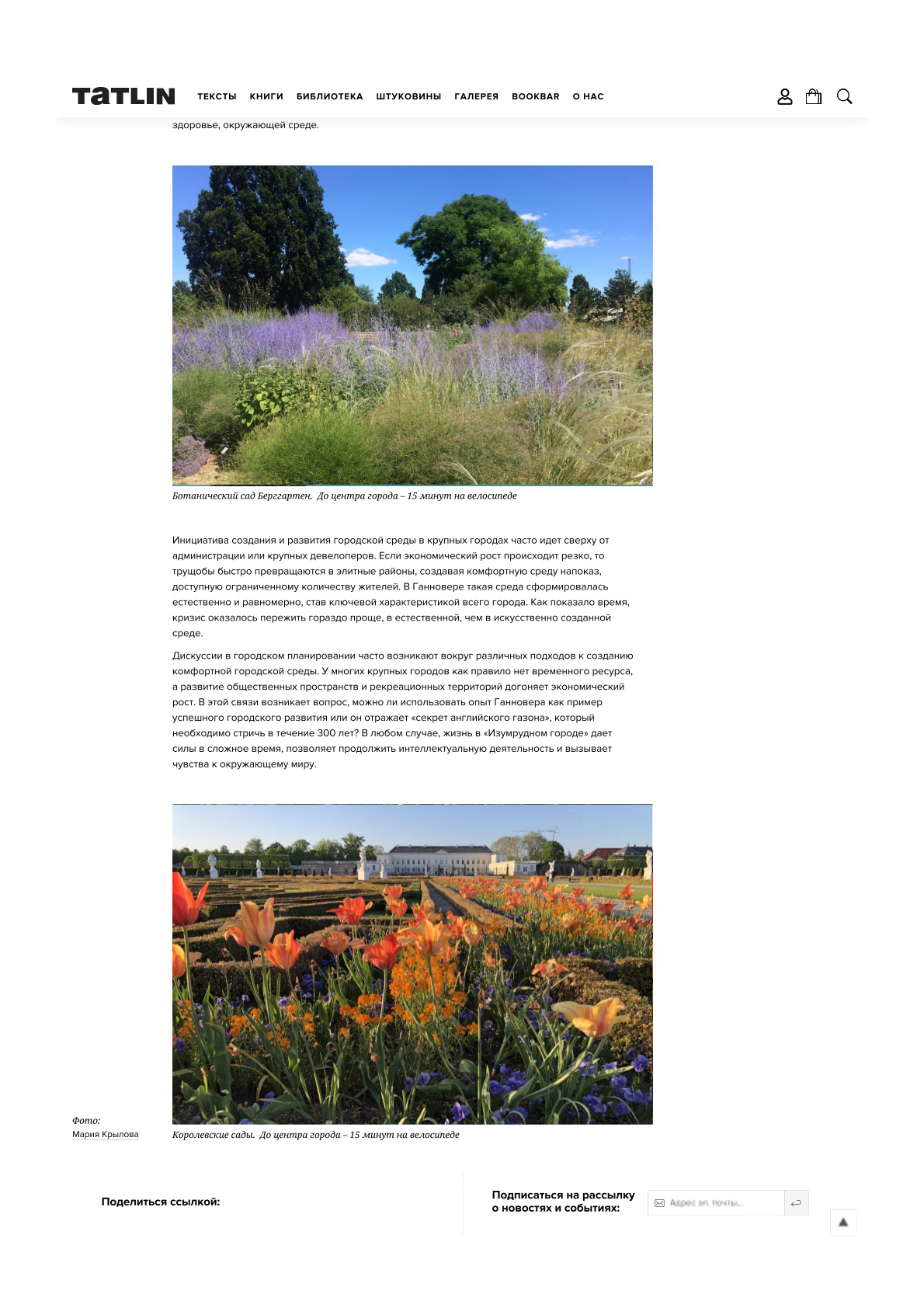

Fig. 23. Berggarten Botanical Garden. 15 minutes by bicycle from the city center.

Initiatives to create and improve urban environments in major cities are often driven from above — by administrations or large developers. When economic growth occurs too rapidly, slums are quickly transformed into elite districts, creating a comfortable environment for display but accessible only to a limited number of people. In Hannover, however, such an environment developed naturally and evenly, becoming a defining characteristic of the whole city. Time has shown that crises are far easier to endure in a natural rather than an artificially constructed environment.

Debates in urban planning often revolve around different approaches to creating a comfortable urban environment. Many large cities lack time, and the development of public and recreational spaces often lags behind economic growth. In this context, one might ask whether Hannover’s experience can serve as an example of successful urban development, or whether it represents the “secret of the English lawn”, which must be “just” tended for three hundred years. In any case, life in this Emerald City gives strength in difficult times, allows intellectual work to continue, and rekindles one’s appreciation for the surrounding world.

Fig. 24. Royal Gardens. 15 minutes by bicycle from the city center.

The full text is published in TATLIN journal (in Russian)